Anup Koushik Karavadi and Kanishk Tiwari

Introduction

The World Trade Organization (WTO), established in 1995, replaced the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which began in 1947. GATT set early rules for international trade but functioned mainly as a diplomatic arrangement, lacking strong enforcement mechanisms. The WTO carried forward GATT’s principles, referred to as “GATT 1994,” and introduced a more robust system through the Dispute Settlement Understanding (DSU). This new framework allowed for binding decisions and an appeals process, transforming trade disputes into a structured, legally enforceable process (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, GATT Overview; Matsushita et al., The World Trade Organization: Law, Practice, and Policy, 2017).

The DSU has been widely praised for providing clear resolutions, consistent rulings, and incentives for countries to comply, a significant improvement over GATT’s weaker system. However, recent challenges have undermined these advancements, pushing the WTO back toward GATT’s inefficiencies. Since 2019, the United States has blocked the appointment of new members to the WTO’s Appellate Body, the group responsible for reviewing appeals. Without enough members, the Appellate Body cannot function, allowing countries that lose disputes to file appeals that go nowhere, effectively stalling decisions. This mirrors the gridlock of the old GATT system, where countries could block unfavourable outcomes (Matsushita et al., 2017).

This situation has serious consequences. The DSU was designed to resolve trade disputes fairly, relying on rules rather than political influence. With the appeals process paralyzed, trust in the WTO is weakening, and some countries are resorting to independent actions, such as imposing tariffs without a multilateral agreement. To address this, several WTO members created the Multi-Party Interim Appeal Arbitration Arrangement (MPIA) in 2020, using a provision in the DSU to maintain an appeals process among themselves. While creative, this solution is limited, as major economies like the United States do not participate, leaving the WTO’s system fragmented (WTO Document JOB/DSB/1/Add.12, 2020).

This ongoing crisis highlights the fragility of global trade cooperation when key members disengage, threatening the stability and fairness of international trade rules.

The Appellate Body Crisis in Practice

Since December 2019, the World Trade Organization’s Appellate Body, often called the crown jewel of its dispute settlement system, has been stuck in a rut. The United States blocked new judge appointments, leaving the body with fewer than the three members needed to hear appeals. What began as a political spat over the Appellate Body’s rulings has snowballed into a full-blown crisis, grinding the system to a halt. The fallout is as simple as it is brutal. When a country loses a WTO dispute, it can file an appeal. But with no functioning Appellate Body, these appeals vanish into a procedural black hole, aptly dubbed appealing into the void. It’s become a go-to tactic for governments looking to dodge unfavorable rulings without breaking a sweat.

Take the US Steel and Aluminium Products case (DS544). In 2022, WTO panels ruled that U.S. national security tariffs violated global trade rules. The U.S. promptly appealed, knowing full well there was no one to hear it, leaving the ruling unenforceable. The same thing happened in India ICT (DS582), where India’s tariffs on tech products were challenged by the EU and others. India appealed the panel’s findings into the void, stalling any resolution. This isn’t a one-off. Between 2020 and 2024, 24 out of 38 panel reports got trapped in this limbo, according to WTO records.

The ripple effects are shaking the foundations of global trade. For one, the system is fracturing. Some countries grudgingly accept unenforceable panel reports, while others sidestep the WTO entirely, cutting bilateral deals or slapping on retaliatory tariffs. This undermines the WTO’s role as the go-to referee for trade disputes. Worse still, without appellate reviews to iron out inconsistencies, panel rulings are all over the map, creating a patchwork of legal uncertainty. The predictability that once made WTO law a cornerstone of global commerce is fading fast.

Then there’s the compliance problem. With no final rulings to enforce, countries have little reason to align with WTO rules. This isn’t just a technical glitch. It’s eroding trust in the entire multilateral trading system. The DSU, once a beacon of fair play, is starting to feel like a relic.

In short, the Appellate Body’s paralysis has turned the WTO’s dispute system into a shadow of its former self. By leaning on appeals into the void, countries are slipping back into the kind of power-driven, tit-for-tat bargaining the WTO was built to replace. It’s a messy step backward, and without a fix, the cracks will only deepen.

Alternatives and Experiments

The WTO’s Appellate Body has been frozen since December 2019; countries have had to get creative to keep trade disputes moving. One standout solution is the Multi-Party Interim Appeal Arbitration Arrangement, kicked off in 2020 by the EU and a group of allies under Article 25 of the Dispute Settlement Understanding. The idea was to mimic the Appellate Body’s role for willing participants, ensuring binding rulings even without a functioning appeals court.

The MPIA got its first real test in 2022 with Colombia Frozen Fries (DS591), where the EU challenged anti-dumping duties on frozen fries from Belgium, Germany, and the Netherlands. The arbitration wrapped up quickly, delivering a decision that felt a lot like the Appellate Body’s style, giving members some much-needed consistency and predictability. The MPIA’s strengths are clear: it keeps appellate review alive for those who sign on, speeds up report adoption, and proves that stopgap solutions can work. But it has a big flaw: it’s not universal. Heavyweights like the United States and India aren’t part of it, so disputes involving them often hit a dead end with no appeal mechanism.

Beyond the MPIA, some countries have tried other workarounds. For instance, in 2022, the EU and Turkey set up an ad hoc arbitration under Article 25 for Turkey Pharmaceuticals (DS583), bypassing the MPIA entirely. These experiments show that WTO members are willing to think outside the box, but they also highlight how patchy the system has become.

Looking at other international courts offers some perspective. The International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) uses annulment committees for a narrow review, focusing only on major procedural errors rather than rehashing the whole case. This keeps things efficient but sacrifices deeper legal scrutiny. The International Court of Justice faced its own crisis in the 1980s when the U.S. rejected its jurisdiction after the Nicaragua case. The ICJ pulled through with reforms and recalibrated expectations, proving that institutions can adapt. The Permanent Court of Arbitration also shows flexibility, letting states and private parties craft custom procedures, though this can lead to inconsistent outcomes.

These examples point to a tough trade-off. Temporary fixes like the MPIA and ad hoc arbitrations keep dispute resolution alive, but they risk turning the WTO into a collection of exclusive clubs. This fragmentation might buy time, but it chips away at the universal authority that made the WTO’s system so strong. Without a broader solution, the multilateral trading order could lose its shine for good.

The Legitimacy of U.S. Actions

The United States has been the loudest voice criticizing the WTO’s Appellate Body. It argues that the body oversteps its bounds. The U.S. claims the body reads obligations into agreements that countries never signed up for. It treats past rulings as binding precedent despite WTO rules saying otherwise. It also drags its feet past the 90-day deadline for issuing reports. For Washington, these flaws justified blocking new judge appointments. This effectively shut down the Appellate Body since 2019. But when you stack this strategy against WTO law and its underlying principles, it raises serious questions about legitimacy.

The DSU sets a clear goal in Article 3.2. It aims to provide security and predictability for global trade. The Appellate Body’s paralysis does the opposite. It sows uncertainty and lets power politics creep back in. Article 17 of the DSU makes appellate review a core part of the process. This ensures disputes get a final resolution. By starving the body of judges, the U.S. has sidestepped this obligation. It leaves countries without the closure they expected when they joined the WTO. In broader international law, the principle of pacta sunt servanda means agreements must be kept in good faith. This suggests that crippling a key institution like this violates the spirit of the deal. It may even skirt the letter.

A case from the WTO’s past sheds light on this. It is US Section 301 Trade Act (DS152), decided in 1999. Back then, the EU challenged U.S. laws allowing unilateral trade retaliation. The WTO panel found that such moves clashed with the multilateral system. It stressed that enforcement belongs in the WTO’s dispute process, not in national hands. The irony is sharp. The U.S. was once called out for bypassing multilateral rules. Now it is undermining the same system by ensuring appeals go nowhere. It is a repeat of the same mindset. This prioritizes control over cooperation.

Legally, this approach does not square with WTO rules. These rules demand a working appellate process and a good-faith commitment to the system. Morally, it is damaging. It erodes trust and tempts other countries to bend or ignore their obligations. The result is a fractured system where consistency takes a hit. But geopolitically, the U.S. strategy makes a certain sense. As the world’s trade heavyweight, it can weather the backlash while shielding its policies from binding rulings. It is a calculated move to keep flexibility and leverage. This is especially true when other countries rely on access to U.S. markets. The cost, though, is a multilateral trading system that is starting to look more like a free-for-all.

Probable Solutions

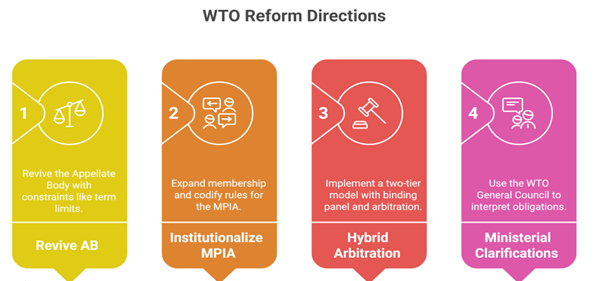

The WTO’s Appellate Body remains paralyzed, driven largely by U.S. concerns over judicial overreach. To restore a functioning dispute settlement system, members must pursue reforms that address these criticisms while upholding the multilateral framework. Below are four practical solutions, presented as a roadmap to balance the WTO’s rules-based system with political realities.

- Revive the Appellate Body with Targeted Reforms:

Bringing the Appellate Body back requires changes that rebuild trust, particularly with the U.S. Fixed-term limits for members could prevent entrenched judicial perspectives and reduce accusations of activism. The mandate should be tightened to focus solely on interpreting agreed-upon texts, steering clear of perceived lawmaking. Enforcing strict timelines for issuing reports would address delays that have frustrated members like Washington. Additionally, treating past rulings as guidance rather than binding precedent would allow flexibility while maintaining consistency. These reforms aim to create a streamlined, accountable appellate process that aligns with members’ expectations. - Formalize the Multi-Party Interim Appeal Arbitration Arrangement (MPIA):

The MPIA, a temporary plurilateral mechanism under Article 25 of the Dispute Settlement Understanding, offers a viable alternative. Its first award in the EU-Colombia dispute over anti-dumping duties on frozen fries (DS591) proved it can deliver efficient, consistent outcomes aligned with WTO jurisprudence. By expanding membership and integrating MPIA rules into the Dispute Settlement Understanding, members could establish a stable, long-term appellate solution. This approach ensures appellate review persists, even if the Appellate Body remains stalled. - Adopt a Hybrid Appellate Arbitration Model:

A hybrid model could combine binding panel decisions with optional appellate arbitration. Panel rulings would form the first tier, with parties able to choose arbitration for appeals if both agree. This setup provides flexibility: members who value appellate review can opt in, while others can rely on single-tier outcomes. By accommodating diverse preferences, this model could bridge gaps among WTO members and sustain a functional two-tier dispute settlement system. - Use Authoritative Interpretations to Clarify Obligations:

Article IX:2 of the WTO Agreement allows the Ministerial Conference or General Council to issue authoritative interpretations of WTO rules. By clarifying obligations upfront, members can narrow the scope for disputes and reduce perceptions of judicial overreach. This approach strengthens political oversight, ensuring the dispute settlement system reflects members’ intentions rather than leaning heavily on judicial interpretation. It offers a path to rebalance the system toward greater political control.

Moving Forward

In the near term, scaling up the MPIA and encouraging broader participation can foster trust and momentum. Over time, negotiations should aim to revive a reformed Appellate Body with constraints that address U.S. concerns. The challenge is to preserve the WTO’s rules-based foundation while navigating the political dynamics of its most influential member. These solutions provide a clear path to restore confidence and functionality to the dispute settlement system.

Conclusion

The WTO’s Appellate Body, once hailed as the cornerstone of its dispute settlement system, remains paralyzed, largely due to U.S. objections to perceived judicial overreach. This crisis has left the system adrift, with panel reports vulnerable to being appealed into a void, rendering them unenforceable and undermining the WTO’s promise of predictability and fairness. The situation has sparked concerns about a return to the less structured, politically driven GATT era, eroding the legal certainty that defined the WTO’s strength.

Efforts to address the crisis have shown mixed results. The Multi-Party Interim Appeal Arbitration Arrangement, tested in the EU-Colombia dispute over anti-dumping duties on frozen fries (DS591), offers a workable interim solution. It delivers efficient appellate review under Article 25 of the Dispute Settlement Understanding, providing stability for its participants. However, major players like the U.S. and India remain outside its framework, limiting its reach. While the MPIA is a promising step, it cannot fully replace a multilateral appellate mechanism.

The U.S. decision to block new Appellate Body appointments sits at the heart of the issue. This stance conflicts with the WTO’s core principles: Article 3.2 of the Dispute Settlement Understanding emphasizes security and predictability, and Article 17 mandates appellate review. By halting the Appellate Body, Washington challenges the good-faith commitment to agreements upheld by the Vienna Convention (Article 26). The irony is striking, given the WTO’s 1999 ruling against U.S. unilateralism in the Section 301 case, which urged reliance on multilateral processes that the U.S. now undermines.

Restoring the system requires a pragmatic, phased approach. In the short term, expanding the MPIA’s membership and refining its processes can maintain appellate review for willing members. Long term, reviving a reformed Appellate Body with clearer mandates, stricter timelines, and flexible precedent rules is essential to regain trust, particularly from the U.S. Without bold reforms, the WTO risks fading into irrelevance, losing the legitimacy that made it a pillar of global trade. The challenge is clear: rebuild a system that upholds rules while addressing the political realities of its most influential member.